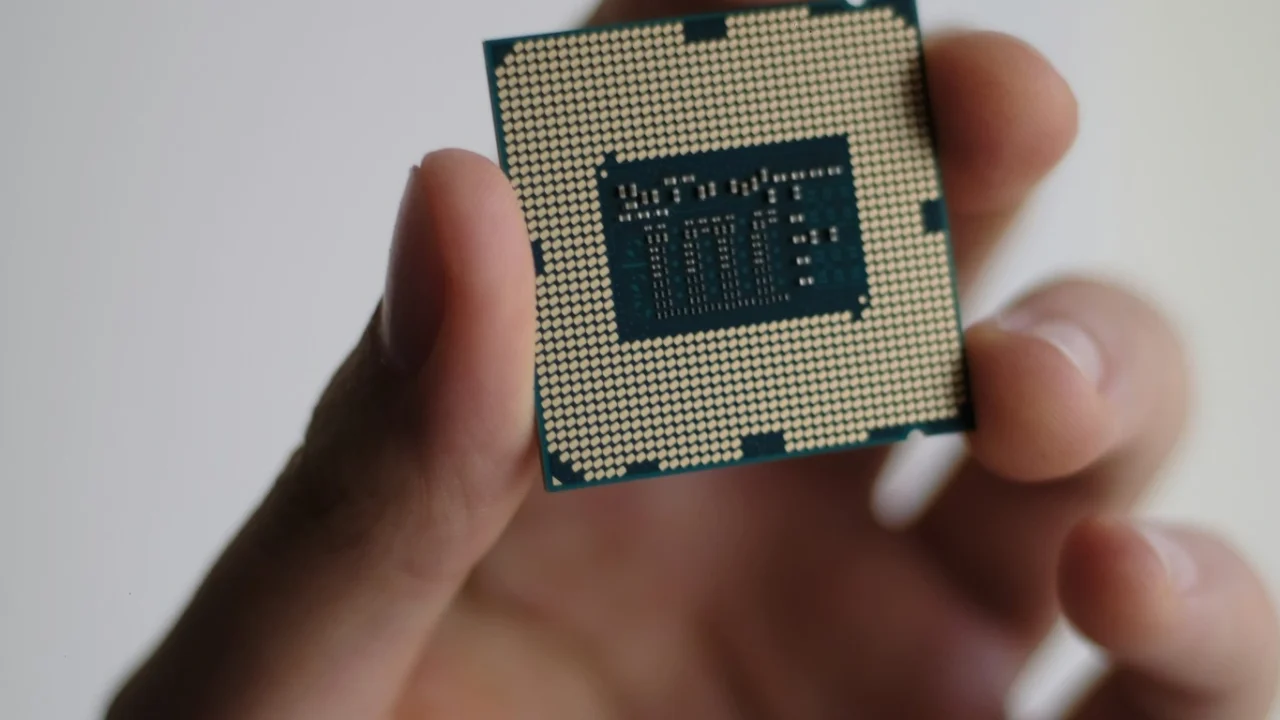

Microchips are some of the smallest mass-produced items today, but they play a big role in how quickly technology advances. Better chips mean thinner phones, cheaper AI, safer cars, and more automated factories. But when chips are limited by physics, manufacturing challenges, or supply issues, entire product plans can be delayed.

This big impact comes from a simple idea Gordon Moore described years ago: integrated circuits improve by cramming more components onto integrated circuits, and this process changes what technology can do. Microchips are small not just in size, but also in how they pack complex engineering into a tiny space, fitting inside almost anything with a power button.

However, the factors that make chips so powerful also make them vulnerable as drivers of innovation. The semiconductor industry has relied on scaling, or shrinking transistors to fit more on a chip. But now, as scaling slows, costs go up, and new tasks like AI need more computing power, bandwidth, and memory, the industry faces new challenges.

From “components” to transistors to systems

At the heart of a microchip is the integrated circuit: a dense arrangement of devices and interconnects that processes and stores information. Moore’s foundational argument wasn’t just that chips would improve; it was that the number of components on a chip would rise sharply over time, making electronics smaller, cheaper, and more capable. That trend became shorthand as Moore’s Law, but its practical meaning is broader: chip progress has historically delivered a compounding effect, enabling each generation to enable new product categories and business models.

Transistor scaling drives this progress. According to a technical overview, Dennard scaling pioneered the progress by showing that making transistors smaller, and adjusting things like supply voltage, could lead to lower area, delay, and power dissipation for MOSFETs. For most of computing history, this meant that smaller transistors usually made chips faster and more efficient without raising costs.

As chips improved, computing architectures also evolved. A survey of CPU and GPU design trends describes how Moore’s Law and Dennard Scaling charted a promising future for computers, and ties shrinking process sizes to increasing capability without consuming more energy. This is the reason microchips produce macro results, it is when the “device” becomes more capable per unit of energy and cost, everything built on top—software, networks, services—can scale with it.

But microchips are just one part of a bigger system. They work alongside memory, storage, networking, sensors, and power supplies. That’s why today’s chip plans focus on devices and systems, not just transistors. The International Roadmap for Devices and Systems (IRDS) 2024 “More Moore” roadmap connects current demand to system changes as big data requires abundant computing, communication bandwidth, and memory resources, and points out that the need for data next to compute accelerated as AI workloads increased. So, the big impact now is not just about fitting more logic onto a chip, but also about getting data to it quickly and reliably.

Why shrinking gets harder every generation

If making chips were only about physics, progress would be about finding smaller switches. In reality, making chips is also a manufacturing challenge, where improvements depend on reliable, high-yield processes across huge supply chains. That’s why roadmaps are important: they help set expectations for devices, materials, manufacturing methods, packaging, reliability, and measurement.

Manufacturing challenges become more visible as scaling tightens tolerances. The IRDS “More Moore” team describes its role in providing physical, electrical, and reliability perspectives for continued scaling. When transistors become extremely small, variability, defects, and reliability risks can rise, demanding not just better design but better measurement and control.

Microchips have a big impact because every new generation needs progress in many areas at the same time, like materials science, process engineering, design automation, and system integration. When these advances come together, we get cheaper computing, smarter devices, and new uses. If they don’t, innovation slows down.

When “More than Moore” becomes the strategy

A key reality of modern semiconductors is that scaling alone can’t reliably deliver every improvement users expect. The semiconductor industry has acknowledged this directly. In the International Technology Roadmap for Semiconductors (ITRS) 2.0 heterogeneous integration chapter, the roadmap states that nowadays, scaling alone does not ensure improvement of all four items, referring to the historic quartet of performance, power, size, and cost. That line is a pivot point as it explains why chip innovation has broadened from shrinking transistors to integrating more functionality at the package and system level.

The roadmap calls this new direction “More than Moore” and talks about tighter integration of system level components at the package level. This is how microchips become platforms for bigger innovations. Rather than focusing only on smaller transistors, companies now combine different chips, accelerators, memory, and specialized parts into one package to get new features and better efficiency.

Recent research supports this trend. A 2025 MDPI paper says that the through-silicon via (TSV) is regarded as the core enabling technology for three-dimensional integration, and calls it a promising solution for continuing the development path of ‘More than Moore.’ In other words, packaging and 3D integration are now key ways to keep improving performance and efficiency, even as making transistors smaller gets harder and more costly.

Why AI makes chips feel even more “macro” than before

AI has not just increased demand for chips; it has changed what good chip design means. Large models and data-intensive workloads reward memory bandwidth, fast interconnects, and specialized compute. This is why the IRDS 2024 document emphasizes that big data needs abundant computing, communication bandwidth, and memory resources, and notes accelerating demand for data next to compute as AI workloads rise.

In practical terms, this pushes chip design toward heterogeneity: general-purpose CPUs paired with GPUs, NPUs, custom accelerators, high-bandwidth memory, and sophisticated packaging. It also amplifies the importance of reliability and power delivery. As chips become more powerful, more heat must be managed, and more energy must be delivered efficiently—constraints that shape everything from smartphone thermals to data-center layout.

What society gains, and what it pays for chip progress

The big benefits of microchips—like speed, convenience, automation, and intelligence—also come with trade-offs that are getting harder to overlook.

One trade-off is economic: adding more components to chips gets more expensive over time. Moore’s original idea was that higher density could lower the unit cost as more components were added. Today, that’s still true, but the initial costs of advanced manufacturing are huge, which makes the industry more concentrated and harder for new companies to enter.

Another trade-off is in design: when Dennard-style scaling stops giving easy power savings, it’s harder to boost performance. Technical discussions say that scaling size and voltage results in lower area, delay, and power dissipation, so when this slows down, it changes everything. The usual answer has been to use more cores, more accelerators, and more complex software, but this makes design harder and puts more pressure on engineers and developers.

A third trade-off is at the system level: combining different types of chips can bring new benefits, but it also creates new challenges in testing, heat management, and reliability. Even though 3D integration is called a promising solution, making reliable and high-performance 3D circuits is still a big challenge. In short, “More than Moore” brings new opportunities, but also new risks.

What microchips really represent in 2026-era innovation

Microchips are not just components. They are the physical substrate of modern innovation—a compact way to convert research breakthroughs into mass-produced capability. Moore’s argument about cramming more components explains why chips historically delivered compounding progress; Dennard-style scaling explains how that progress stayed energy-feasible; and modern roadmaps like IRDS and ITRS show why the industry is now expanding the playbook beyond transistor shrinking.

The most important lesson is that chip progress is becoming more multidimensional. As IRDS frames it, the growth of AI workloads intensifies the need for data next to compute, shifting attention toward memory, interconnects, and system design. Meanwhile, ITRS’s warning that scaling alone does not ensure improvement is, in effect, a public declaration that packaging, integration, and specialization are now core innovation strategies, not side projects.

Here’s one simple way to think about microchips and their big impact: the chip is where physics turns into products. When chip development moves forward, whole industries grow. When it slows down, everyone feels it.

Where the next “macro results” may come from

The next big advances will probably come from combining several approaches, not just one. Scaling will still be important, but so will “More than Moore” integration at the package level, and new technologies like TSV-based 3D integration. The leaders may be the companies and countries that see microchips as part of a whole system—devices, packaging, manufacturing, and software working together to meet real-world needs.

In this new environment, the biggest microchip breakthrough might not be a single transistor. Instead, it could be the ability to turn tiny switches into reliable, affordable, and world-changing machines through smart system design.